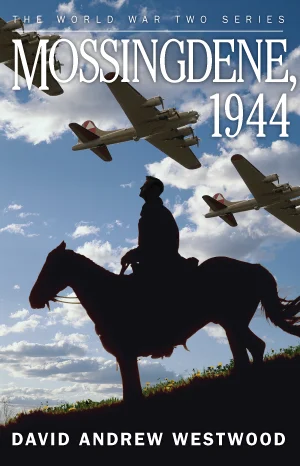

MOSSINGDENE, 1944

Book VII of the World War Two Series

Fiction: war/adventure/historical romance

A remote village in England, filled with Allied soldiers far from home, all of them poised on the brink of invading Europe. Into this volatile mix come three strangers: Eddie, bad boy from the wrong side of the tracks in Los Angeles, who avoids jail by signing up as a gunner in an American bomber unit. Dot and her two singer sisters are bombed out of the family’s London home and evacuated to work on their aunt’s farm. Scotsman Duncan, his mother held by the Nazis in Dachau, is blackmailed to spy on Allied invasion plans.

Inevitably, their lives become entangled. Both Duncan and Eddie fall in love with Dorothy. Eddie’s bombing flights become ever more dangerous, and he knows he can’t live for much longer. Dot’s career takes off when the trio’s first record becomes a hit, and suddenly they’re “the voices of World War Two.” Duncan is increasingly desperate to uncover something to placate Berlin before he and his family are annihilated.

And the authorities know someone is transmitting from the village.

Pre-invasion Britain Facts

By 1944 the war had palpably turned in favor of the Allies. The Axis was on the defensive, but not prepared to submit to unconditional surrender. Vast numbers of British bombers were raiding Germany and its territories by night, and the U.S. Army Air Force was bombing by day. Nevertheless, it was becoming clear that bombing was not enough, and that the mainland of Europe would have to be invaded and Germany beaten by ground troops on its own turf.

Britain’s midlands and south had thus become a staging ground for D-Day, filled with thousands of American troops and their materiel, as well as all the British and Commonwealth troops that could be mustered. At first relations were cordial, but as numbers increased, so did the tension between the two cultures. Britain needed America’s help, but the influx of so many Americans became problematic.

Hitler had been developing ‘vengeance’ weapons for last resort use, and these were now released on Britain, in a second, vicious, Blitz.

Sample chapter: © David Andrew Westwood 2010, all rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without written permission from the author.

28. Duncan.

Everton, England, May 1944

Duncan had a pint or two too many at The Thornton Arms, Everton, across the county border into Bedfordshire. He’d run into a fellow Scot, a Dundee man, shared memories over a few drinks, and lost track of time. Now Duncan was hoping Nutmeg could find her own way back. This was the farthest either he or the horse had been from Kemp’s stables in their explorations, and now that it was dark, a dark unrelieved by any light except a full moon peeping occasionally through clouds, he was a little lost.

His head was buzzing, and at first he thought the odd sound came from inside his skull. But it rapidly became clear that an engine, a spluttering engine, was coming closer. He squinted ahead along the road, then behind, over the horse’s back. Nothing. Then he looked up. From the direction he was heading came a black shape trailing ghostly gray smoke.

It was an aircraft in distress. Its motor was cutting in and out, and it appeared to be having trouble staying aloft.

As it passed him a couple of hundred yards to the left Duncan saw the indistinct shapes of the two people in the long cockpit. Then it sank onto a field with a muffled crump.

“Whoa ree!” yelled Duncan, snapped sober, digging his bootheels mercilessly into the horse’s flanks. She responded by smartly turning left, and he got her into an almost-gallop by the time they’d reached a spot in the road nearest the crash. He urged her through the hedgerow, and Nutmeg tiptoed carefully onto the planted field and then refused to go any farther, snorting at the smell of aviation fuel and oil. Duncan slid down to the soft earth and ran toward the dark, hissing form.

As he came close Duncan recognized the distinctive shape of another Lysander. The dragonfly-shaped wings that passed through the top of the cockpit, the fat spats over the wheels, though the metal bracket unit that held the undercarriage had cracked in half on impact.

There was no fire, just smoke and steam.

No one was visible in the cabin, and Duncan peered into the front section. The pilot was obviously dead, slumped over the stick, his head at an odd angle and a lot of blood around holes in the back of his jacket.

He turned to the cockpit’s rear. Inside was a young woman, eyes closed, head back and mouth open. He checked her pulse. She was breathing shallowly.

Duncan looked around in desperation. There were no houselights to be seen. He leaned back inside to the woman and squinted, gleaning details. She wore a smart, European-styled suit, probably light gray or blue. In her pockets he found a packet of Gauloises, some aluminum francs and a small comb. On the floor of the cockpit he found a handbag and looked inside. In the dark he couldn’t see much, but the moonlight showed what was clearly a French passport and some papers, along with a powder compact and a handkerchief. On an impulse, he pocketed the documents.

Now he’d better find some help. He thought he remembered passing a telephone kiosk by the side of the road as he left the last village. He remounted the horse and urged her out to the road and back in the direction they’d come.

In a few minutes he saw the phone box and dismounted by its side. But it was chained with two loops of stout link and secured with a fist-sized padlock.

Duncan stared with incomprehension. He’d never seen anything like this. It made no sense. Perhaps at the opposite end of the village there was another. He jumped back on Nutmeg and kicked her forward. She was balky now, but the sense of urgency had been communicated to her and she did his bidding.

There was, indeed, a box at the end of the hamlet, but before Duncan reached it he saw another chain, glinting dully. What was all this about?

All right: A doctor? He doubted there’d be a physician in this little speck of a place — it didn’t even have a church or a pub. No, his best chance would be to go back and wait by the road until a car came, wave it down, then send them for help. He could also check on the woman, see if there was anything he could do to make her more comfortable.

Back down the lane they cantered, the horse’s shoes ringing on the road’s surface, loud in the otherwise quiet night. As they neared the crash site he saw lights, and thought with relief that someone had called an ambulance and everything was under control. But as he rode nearer he saw soldiers across the road and filling the field, rifles raised. An RAF ambulance was bouncing slowly across the ruts, back to the road.

“Move along there,” said one of the men, a colonel.

A colonel? “What happened?” Duncan couldn’t resist asking, even though by now he had a pretty good idea: An agent had been picked up in France, her plane had been shot at by a Luftwaffe night fighter, and it had crashed short of its base.

“Never you mind,” said the colonel, with hostility. “Move along now — smartish.”

Well, that was it, thought Duncan. For the RAF to have arrived so quickly they must have already been very close to the crash. That meant that the undercover squadron’s base was nearby. He must have spent the night drinking at their local pub.

And the locked phone boxes? Britain’s telephone system was notoriously insecure. The military must be making an unsubtle attempt to stop agents from making last-minute phone calls to family and spouse that could compromise the mission if overheard.

He rode on. Tomorrow he would return.

* * *

Duncan studied the passport in the dim yellow light of his oil lamp. It was for Patrice Rocault, born in Soissons in 1917. Her papers, approved by the Vichy government’s rubber stamps, allowed her to travel as a fabric saleswoman for Tissus Picardie. Another sheet appeared to be a typed order on Henri Cammarle et Cie of Amiens letterhead, for, if his school French served him correctly, a dozen bolts of fine summer weight wool. And a third sheet showed a hand-drawn map of Northern France with Xs at spots that were carefully named. He had no idea what they represented.

But he finally had something to report. He made a quick tour of the stables — Nutmeg was exhausted and tried to bite him — and then went upstairs. Once the radio was warmed up he tapped

TTTTT LYSANDER CRASHED KILLING PILOT X PASSENGER PATRICE ROCAULT INJURED X PR HAD MAP OF NW FRANCE WITH EPERLEQUES WIZERNES MERY SUR OISE CHATEAU DU MOLAY MARKED X ADVISE X END.

In twenty minutes came the response

RECEIVED X REPLY 04:00 GMT X ENDE.

Another restless night, and then the message

URGENT YOU IDENTIFY LYSANDER AIRFIELD X INVESTIGATE AND REPORT COORDINATES X DESTROY MAP IMMEDIATELY X DO NOT MAKE COPY X ENDE.

Well, they were certainly interested in the map. What the hell did it show? Obviously the sites of something, but what? Some secret weapon? Did Hitler have something new? What map was so important that a pilot had died to bring it back?

But it was not his task to decipher maps. He struck a match and carefully — his room was full of hay and hay dust — went to light its corner. Then he blew out the flame and instead hid the paper above a beam.